Helping parents avoid ‘burnout’ amid extra stress

When families are under stress, especially if parents aren’t aware of how their emotions may impact on their parenting, there may be more friction and anger in the home. This can have a negative impact on tamariki, which can then create more stress.

This isn’t a new phenomenon. But more recently, psychologists have started looking more closely at what’s being called “parental burnout”. This seems to have increased, especially since the pandemic and more so in Western countries (possibly due to less extended family support).

No such thing as ‘the perfect parent’

Perfectionistic parenting, especially if parents often feel doubtful and self-critical, is a risk factor for parental burnout, according to a recent paper published in the journal Current Psychology.

On the other hand, emotional competence – being able to understand, express, and regulate emotions – can counteract the risk posed by perfectionistic parenting. In effect, emotional competence reduces the risk of burnout, the new research has found.

Once again, new research confirms what’s long been established as part of the Triple P – Positive Parenting Program®. Trying to be ‘the perfect parent’ is a known ‘parenting trap’ described in Triple P programmes. Having realistic expectations, of yourself and of your children, is one of the five key principles of Triple P.

Triple P’s self-regulatory model helps parents take a step back, reflect, and get in touch with their own emotions and children’s emotions.

Along the way, parents gain the skills to become independent problem solvers, to monitor their own emotions and behaviour (and children’s emotions and behaviours), and to look for strengths and areas for improvement.

Balancing the ‘stress scale’ by learning new skills

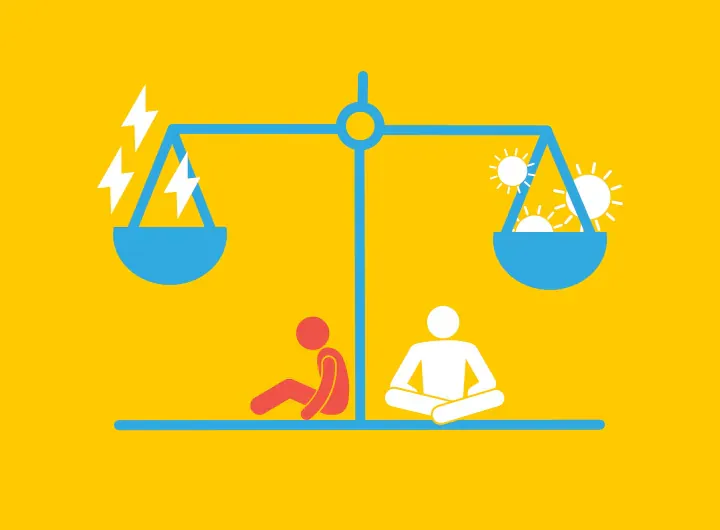

We can think of stress as being on one side of a scale, and resources to deal with stress on the other. Every parent is under stress, and some may be under quite a lot. But as long as there are enough resources on the other side balancing things out, people can avoid becoming ‘burnt out’.

The ‘resources’ that help people cope with stress include things like positive parenting knowledge, coping and relaxation skills, and “emotional competence” as described above.

Nobody’s born with these resources. They’re learned, developed, and improved. So in stressful times, it’s even more important to try to empower as many whānau as possible with such knowledge and skills – which they can also pass on to children.

(The 2021 research paper, which can be found here https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12144-021-01509-w looked at previous research and did two online surveys, one with 347 parents in Belgium and another with 377 parents in Poland.)